| Back to . . . |  The Hyperbola of Fermat: One of the Classic Conic Sections. . . . |

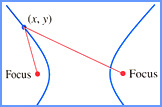

The difference between (x,y) and the two foci remains constant. |

Replay the animation |

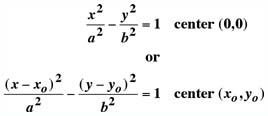

These

equations are in "Cartesian" form. What is less well-known is

that Fermat, not Descartes, might be credited with writing about these

curves earlier than his contemporary. According to E. T. Bell, "...each of them,

entirely independently of the other, invented analytic geometry"

and

labeled Fermat as "The Prince of Amateurs."

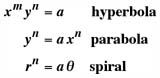

The following are all known as the hyperbola, parabola and spiral of Fermat.  In

a letter written to Roberval in 1636, Fermat stated that he had

formulated these curves seven years earlier.

|

Parametric Plot  Polar Plot  |

The Prince of Amateurs |

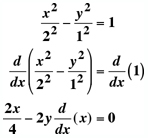

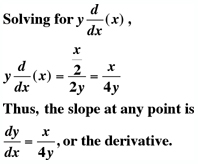

An Example of Implicit

Differentiation from Calculus Applied to a Hyperbola

|

|||

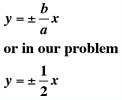

For |

|

Note: Using the slope

of the slant asymptotes, not points on the hyperbola, to sketch a

hyperbola is far

more common and does not require calculus.

|

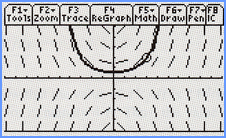

But if the

slope at any point on the hyperbola is known, a "slope field" may be

drawn using a TI-89 or TI-92 Plus. The calculator screen for the

upper branch of a hyperbola might appear as . . . .

|

Other Animated Spirals with MATHEMATICA®Code

Historical Sketch on Spirals

The name spiral, where a curve winds outward

from a fixed point, has been extended to curves where the tracing

point moves alternately toward and away from the pole, the so-called sinusoidal

type. We find Cayley's Sextic, Tschirnhausen's Cubic, and

Lituus' shepherd's (or a bishop's) crook. Maclaurin, best known

for his

work on series, discusses parabolic spirals in Harmonia Mensurarum (1722).

In architecture there is the

Ionic capital on a column. In nature, the spiraled chambered

nautilus is associated with the Golden Ratio, which again is associated

with the Fibonacci Sequence. |

|

|

|||

| http://www-history.mcs.st-and.ac.uk/history/Curves/Fermats.html | |||

| Bell, E. T., Men of

Mathematics, Simon and Schuster, 1937, pp. 56 - 72. |

|||

| Boyer, Carl B., revised by U. C. Merzbach, A History of Mathematics, 2nd ed., John Wiley and Sons, 1991. | |||

| Eves, Howard, An Introduction to the

History of Mathematics, 6th ed,. The Saunders College Publishing,

1990, pp. 353-354. |

|||

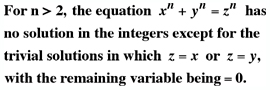

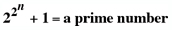

| FERMAT'S THEOREM, math HORIZONS, MAA, Winter, 1993,

p. 11. |

|||

| Gray, Alfred, Modern Differential Geometry of Curves and Surfaces with MATHEMATICA®, 2nd ed., CRC Press, 1998. | |||

| Katz, Victor J., A History of

Mathematics, PEARSON

- Addison Wesley, 2004. |

|||

| Lockwood, E. H., A Book of Curves, Cambridge University Press, 1961. | |||

| McQuarrie, Donald A., Mathematical

Methods for Scientists and Engineers, University Science Books,

2003. |

|||

| Shikin, Eugene V., Handbook and Atlas of Curves, CRC Press, 1995. | |||

| Yates, Robert, CURVES AND THEIR PROPERTIES, The National Council of Teachers of Mathematics, 1952. | |||

|

From the

legendary Delian problem in antiquity to modern

freeway construction, spirals have attracted great mathematical talent.

Among the more famous are

From the

legendary Delian problem in antiquity to modern

freeway construction, spirals have attracted great mathematical talent.

Among the more famous are