| Back to . .

.

Deposit #59 |

The Pursuit Family of Curves Possibly originating with Leonardo da Vinci but first extensively investigated by Bouguer in 1732. |

|

|

This

section

features the

Pursuit Curves. One particle travels along a specified

curve, while a second pursues it, with a motion always directed toward

the first. The velocities of the two particles are always in the

same ratio.

Thus, the two beads move with related velocities. When the ratio k of the two velocities is greater than one ( k > 1 ), the pursuer travels faster than the pursued. The question then becomes, "At what point do the two meet?" What is the "capture" point? |

|

Observe the pathways of the two beads representing two particles. The yellow bead pursues the black bead in such a way that the yellow bead on the right is always moving toward the black bead. The yellow bead follows the linear green vector and is always directed toward the black bead. Our MATHEMATICA® animation is for the special case where the pursued always moves in a linear fashion. We find examples in the literature of linear motion along the x-axis. Others have considered vertical motion, either on the y-axis, or parallel to it.

|

|

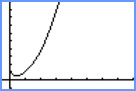

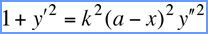

Various forms of the equations for the pursued having linear motion are found in the literature.

|

Historical Sketch:

An excellent overview of the history of pursuit curves is

found in a series of articles written by Arthur Bernhart (University of

Oklahoma) and published in Scripta

Mathematica in the 1950s. He organizes his review into

four categories: pursuit curves where the pursued moves along a

straight line; the chase takes place in a circular fashion; the race

among several competitors is in a polygonal fashion; and finally,

special cases involving dynamical pursuit with variable speeds, centers

of gravity, and other aberrant properties. This series of

articles

cuts across centuries of time, countries and languages.

An excellent overview of the history of pursuit curves is

found in a series of articles written by Arthur Bernhart (University of

Oklahoma) and published in Scripta

Mathematica in the 1950s. He organizes his review into

four categories: pursuit curves where the pursued moves along a

straight line; the chase takes place in a circular fashion; the race

among several competitors is in a polygonal fashion; and finally,

special cases involving dynamical pursuit with variable speeds, centers

of gravity, and other aberrant properties. This series of

articles

cuts across centuries of time, countries and languages.A bit of historical background is fascinating. The publications by Bernhart and several others often begin in antiquity with Zeno's solution to the classic Achilles and the Tortoise, mention the work of Leonardo da Vinci, and then move to a Frenchman, Pierre Bouguer (1698-1758) who expanded pursuit to two dimensions. Interest crossed the border into Italy, where the problem became curva di caccia, and then into Germany where readers will find dachshunds in Hundekurven problems. Across the English Channel a spider was pursuing a fly in the well-known Ladies' Diary (1743,1750 and 1752).

Even readers of a mathematical bent in North America enjoyed "Curves of Pursuit" in the Mathematical Monthly (1859), one of the earliest publications of general mathematical interest on this side of the Atlantic. Professor O. Root of Hamilton College, Clinton, NY published on one dog chasing three foxes. Other early Americans who published on the topic include Artemas Martin. Access to his mathematics collection at the American University in Washington, DC has enriched a number of NSF-MAA sponsored workshops.

Famous 20th century mathematicians who published on pursuit curves include Georg Cantor, the father of set theory, and the top British classical analyst, J. E. Littlewood of the famous team of Hardy and Littlewood. He composed and published an essay on "Lion and Man."

The NCB can only briefly write on the vast and rich literature of pursuit curves. We conclude with the closing from Bernhart's series of articles . . . . .

"And God said,

'Let there be light'; and there was light.' The Hebrew text uses

the same word or the command and its fulfillment. But we can

imagine the angelic architect asking for more details: 'What

path shall light follow in going from P to Q

?' And the answer might have been, 'Don't bother me with

such details. See that it makes the trip in a minimum time.' "

Arthur Bernhart,

"Curves of General

Pursuit", Scripta Mathematica, 24,

p. 206, 1959.

|

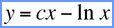

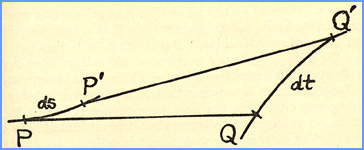

I.

Category One: One

dimensional pursuit in a plane with a linear

track and uniform speeds. Let the point Q move along a given tract Q(t) while another point P moves always in the direction PQ on P(s). If the velocity vector dP/ds has the same sense as PQ, the locus P(t) is called a curve of pursuit, otherwise a curve of flight. |

||||||

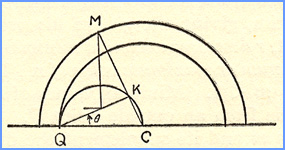

II.

Category Two:

Pursuit curves for a circular track. "A

dog at the center of a

circular pond C makes

straight for a duck which is swimming along the edge of the pond.

If the rate of swimming of the dog is to the rate of swimming of the

duck as m : 1, determine the

equation of the curve of pursuit and the distance the dog swims to

capture the duck." "A

dog at the center of a

circular pond C makes

straight for a duck which is swimming along the edge of the pond.

If the rate of swimming of the dog is to the rate of swimming of the

duck as m : 1, determine the

equation of the curve of pursuit and the distance the dog swims to

capture the duck."C is the center of the pond, Q is the "quacker," and the point of attack is K, which conveniently forms an inscribed right triangle. American Mathematical Monthly, 27 (1920), p.

31

A. S. Hathaway, Houston, Texas |

||||||

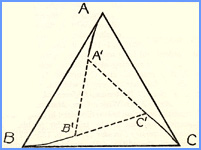

III.

Category Three:

Problems of triangular pursuit. "Three dogs are placed at the three vertices of an equilateral triangle; they run one after the other. What is the curve described by each of them? |

||||||

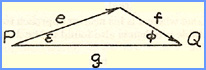

| IV.

Category Four:

Differential equations valid for

arbitrary track and variable speeds; Miscellaneous problems sometimes confused with pure pursuit curves.  "Navigation:

Does one swimmer P

pursue another Q

when his course is

toward Q though

his heading is somewhat

upstream? If P

swims through the water medium at speed e, and the current flows with

speed f at an

angle φ with the desired course PQ, then P must head off course by a

correction angle ε in order to make good his course. "Navigation:

Does one swimmer P

pursue another Q

when his course is

toward Q though

his heading is somewhat

upstream? If P

swims through the water medium at speed e, and the current flows with

speed f at an

angle φ with the desired course PQ, then P must head off course by a

correction angle ε in order to make good his course.

The opportunities for animation of pursuit curves are enormous. The NCB invites faculty and students to try their hand at some of these problems as class projects. Then hopefully you will add a "choice" effort to our NCB MATH Archive collection as a sampler of a fun activity from your campus. |

||||||

|

|

||||

|

For more information on Pursuit Curves: < http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Curve_of_pursuit > |

||||

| For a variety of Pursuit Problems: < http://mathworld.wolfram.com/topics/ApolloniusPursuitProblem.html > | ||||

| For the evolute in

JAVA: < http://www-history.mcs.st-and.ac.uk/history/Curves/Pursuit.html

> Note: The French scientist Pierre Bouguer attempted to measure the density of the Earth by using a plumb line deflected by the attraction of gravity. He collected data on the top of a Peruvian mountain. While he was more or less unsuccessful, the thought that he would attempt this in South America in 1740 is slightly amazing. |

||||

| Gray, Alfred, Modern Differential Geometry of

Curves and Surfaces with MATHEMATICA®,

2nd ed., CRC Press, 1998, pp. 66-69. |

||||

| Wagon, Stan, MATHEMATICA®IN

ACTION, W. H. Freeman and Co. ISBN

0-7167-2229-1. |

||||

| Wagon, Stan, MATHEMATICA®

IN ACTION, 2nd ed., Springer-Verlag, 2000. ISBN

0-387-98684-7. |

||||

| Weisstein, Eric W., CRC

Concise Encyclopedia of MATHEMATICS, CRC Press, 1999, p.1461. |

||||

| Yates, Robert C., Curves and Their Properties, NCTM, 1952, pp. 170-171. | ||||

| One of

the thrills of

visiting the Sistine Chapel in Vatican City is seeing Raphael's The

School

of Athens. His famous frescoes are just outside the doorway

to the Chapel. Among the important mathematical figures

represented are Euclid (see the postage stamp on the right.), Ptolemy,

and Pythagoras. Click on the stamps to see a larger

view of Euclid and his students. In particular, The School of Athens is considered

one of the earliest and finest examples of perspective, a highly

geometrical illusion of giving distance its proper proportion on a

plane surface. |

||||

|

||||